The Legacy of St. Benedict:

Monasticism in the Western Church

Born

about 540 A.D., Benedict was sent to get a liberal education by his wealthy and

distinguished parents. However, once he encountered the dissolute life led by some

students, “in his desire to please God alone, he turned his back on further

studies, left home and inheritance and resolved to embrace the religious life.[1] Some authors have noted that, although

Benedictine spirituality is often associated with learning, its founder was

focused not on formal education, but on a simple life of work and prayer.

One of

the first miracles chronicled by Pope Gregory was an incident that involved

Benedict’s nurse, who had accompanied him in his search for a place to withdraw

from the sinfulness of the world. Having asked to borrow a tray for cleaning

wheat at the house where they were lodging, the nurse accidentally allowed he

tray to fall and break in two. When Benedict returned and saw her weeping, “he

prayed earnestly to God … (and) soon noticed that the two pieces were joined

together again.” [2]

Shortly

after this, Benedict left his nurse and proceeded to Subiaco, where he spent

three years in prayer and solitude. During that time the monk Romanus, who had

clothed Benedict in a simple habit, brought him food and drink. It is in this

period, too, that Benedict experienced perhaps the most famous of his

temptations, in which the devil tried him with lustful images. The young man responded

by throwing himself naked into a patch of nettles so that “the pain that was

burning his whole body had put out the fires of evil in his heart.”[3]

From that day forward, Benedict was free from this kind of temptation and began

to instruct others in the way to live for God.

Another

event in Benedict’s life shows how God intervened to guide him. He and his twin

sister, Scholastica, who had been consecrated to God from an early age, would

meet periodically to encourage one another and pray together. One time when

they had praised God all day and darkness was falling, Benedict, ever mindful

of his vow of stability, wished to return to his monastery. Scholastica

entreated him to stay the night, so they could continue talking and praying

together. When her brother refused, she prayed earnestly and the sky, which had

been clear, clouded over and a great storm arose, making it impossible for

Benedict and his brothers to leave. The siblings spent the night talking of the

joys of heaven and, when Benedict finally reached his monastery the next day,

he had a vision of Scholastica’s soul entering heaven. He then rejoiced at her

glorification, gave thanks to God and brought her body to be buried in a plot

near his monastery. [4]

An often-told story throws light on the virtue of Benedict and his direction of his brother monks. It seems a certain priest, Florentius, who lived in the neighborhood of Benedict’s monastery, observed that the saint had inspired many to a more fervent piety. Seized by envy and hatred for Benedict, Florentius sent him a loaf of bread he had poisoned, hoping to kill his rival. Benedict, however, knew what was in the bread and gave it to a raven to take away.

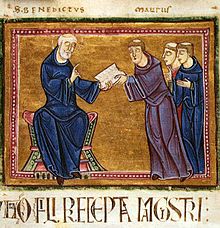

Foiled

in that attempt, Florentius then sent naked dancing girls to compromise the virtue

of the younger monks. Fearing that his monks would fall into temptation,

Benedict took them and left the monastery. As they journeyed away from their

home, God struck Florentius dead when the roof over him collapsed. One of

Benedict’s monks, Maurus, caught up with him and gave him the news, rejoicing

in Florentius’s demise. Benedict reprimanded Maurus severely and gave him a

penance for showing pleasure that another had died unrepentant of his sin.[5]

The fact that Gregory calls Benedict, “vir

Dei,” indicates in what high regard he was held even shortly after his

death.

Eventually

Benedict wrote his rule for all the foundations he had created and it has

remained the standard for much of monasticism up the present day. Modern

historians believe that the Rule of the Master, which is a much longer and more

detailed set of prescriptions for the pursuit of perfection, may have influenced

Benedict, but there are many differences in style and content between the two.

Benedict’s

rule is uncompromising in what is necessary for the pursuit of perfection, but

still gentle in its language. His description of the Abbot is that of a loving father,

who adjusts his methods of direction to the temperament of each monk. The Rule

covers many topics, but in no very discernible order. One part may talk about

the celebration of Lauds on feasts, while shortly thereafter the saint treats

of who shall sit at the Abbot’s table or how absent brethren are to be

received. Nevertheless, it covers most questions and details practices

necessary for a well-ordered community life.

[1]

Pope St. Gregory the Great, Life and

Miracles of St. Benedict (Book Two of the Dialogues) tr. By Odo J.

Zimmerman, O.S.B. Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press,

[2]

Pope St. Gregory the Great, p.3.

[3]

Pope St. Gregory the Great, p. 8

[4]

Pope St. Gregory, pp. 69-70.

[5]

Pope St. Gregory, pp. 23-25.

No comments:

Post a Comment